Executive Summary: The economy is exiting the pandemic-induced recession heading back to its pre-crisis growth path

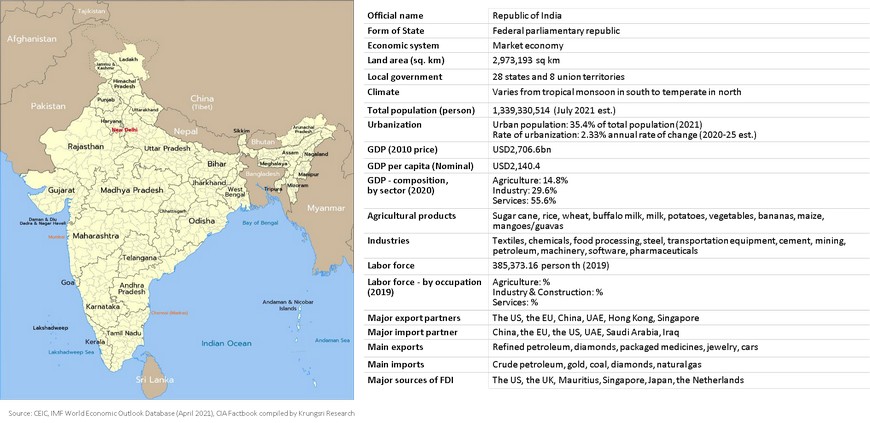

India in brief

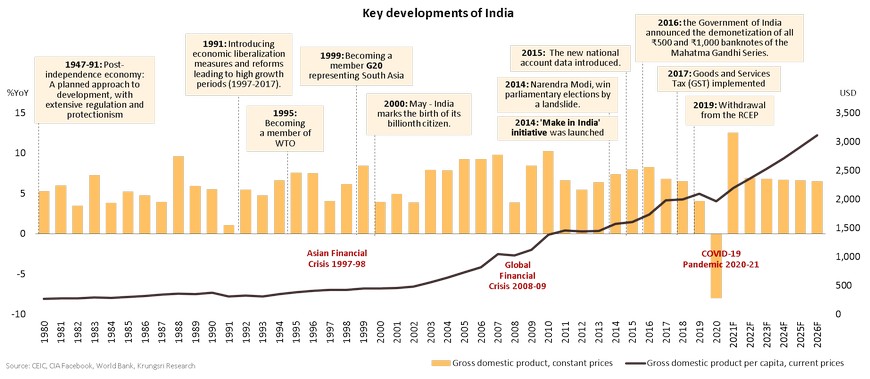

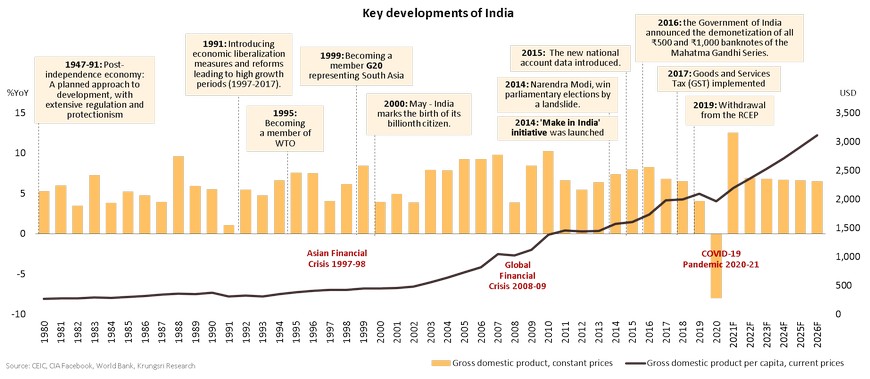

India has enjoyed periods of a sustained high growth of about 7% p.a. due to its economic liberalization towards a market-based economy started in the 1990s

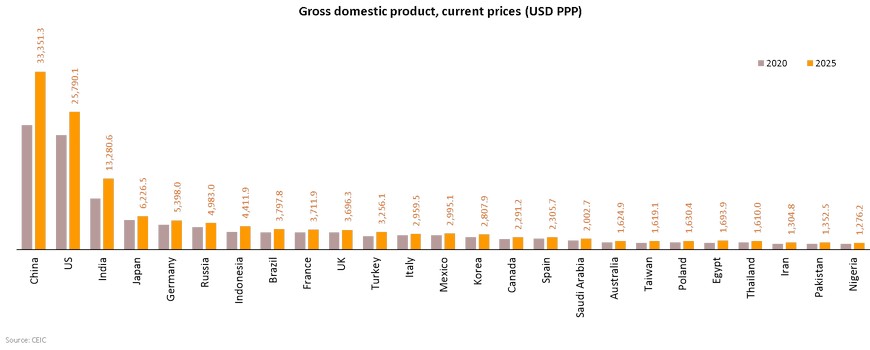

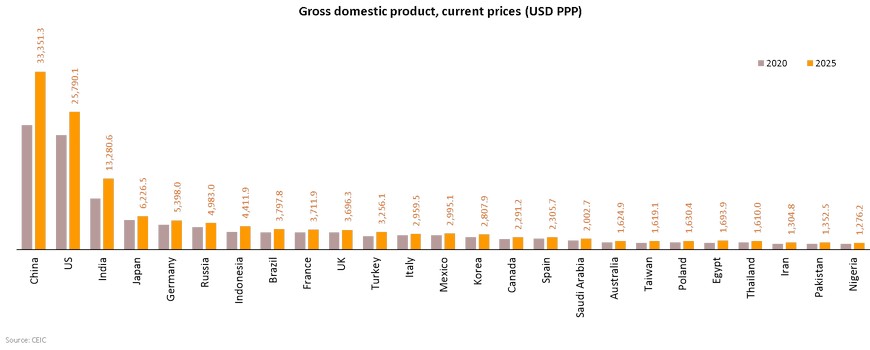

India has witnessed robust economic growth with average rate of 7% over the past three decades. So, the country has been among the fastest-growing economies in the world over the past few years. As a result, India has become the third largest economy in PPP term. Sustained high growth has been driven market-oriented reforms implemented in the 1990s. A series of structural reforms introduced under PM Modi is expected to boost India’s growth over the horizon.

By 2025, India aims to become a USD5-trillion economy through rapid structural reforms

Currently, India is the world's largest democracy and the third largest economy in terms of purchasing power parity. Economic liberalization, including reduced controls on foreign trade and investment, began in the early 1990s, and long‑term GDP growth has become more stable, diversified and resilient. Over the next few years, India is expected to grow strongly, with progress being buttressed by dynamic reforms in the macroeconomic, fiscal, tax and business environments such as introducing reforms on the Goods and Services Tax (GST), as well as by favorable demographics.

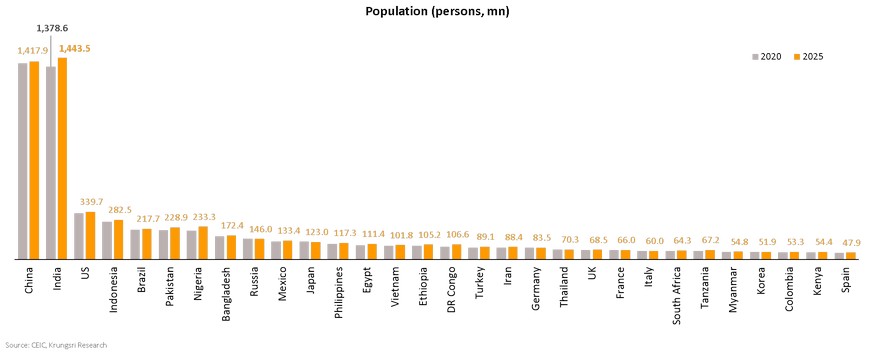

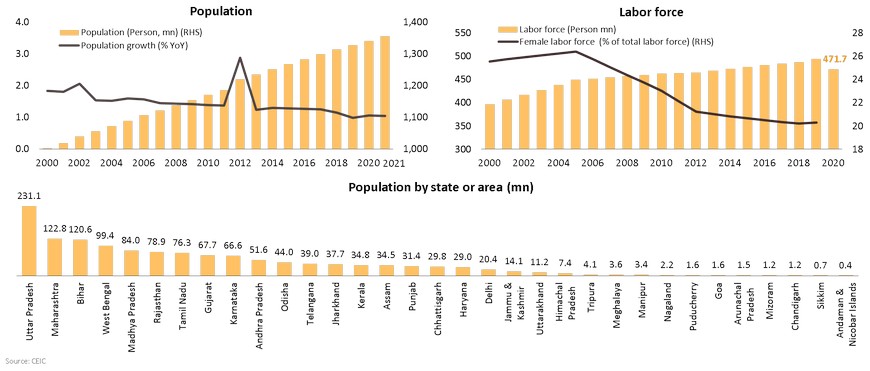

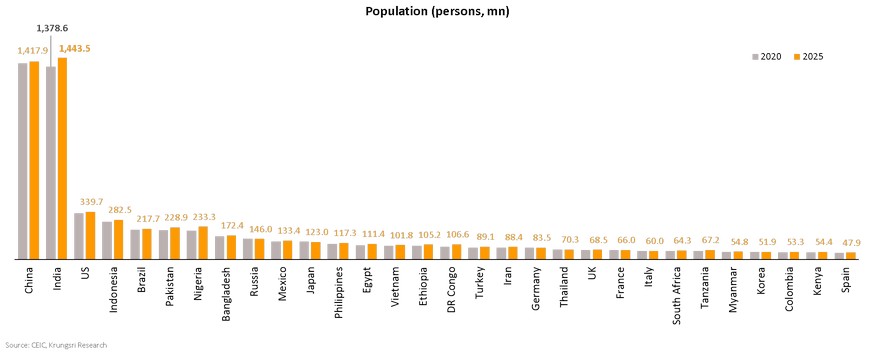

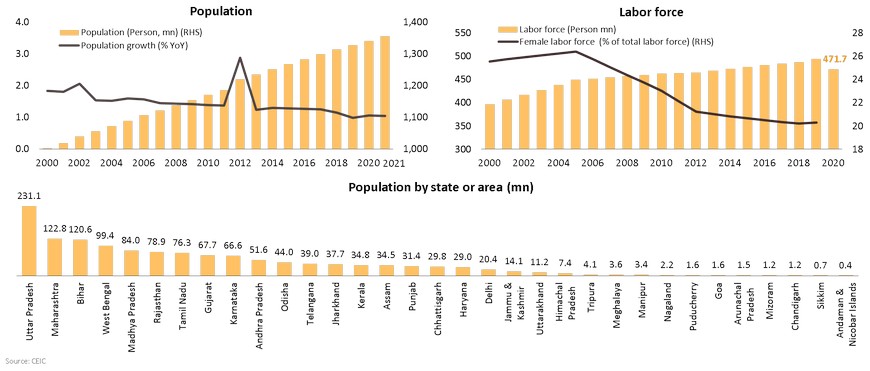

India is projected to be the most populous country with the population size of 1.44 billion by 2025

By 2025, India is expected to take over China as the most populous country with the population size of about 1.44 billion, from the size of about 1.38 billion in 2020. This comes with both opportunities and challenges. On the former, India will become a huge and dynamic market for businesses, and, on the latter, the authorities would need to generate ample job opportunities to absorb young workforce.

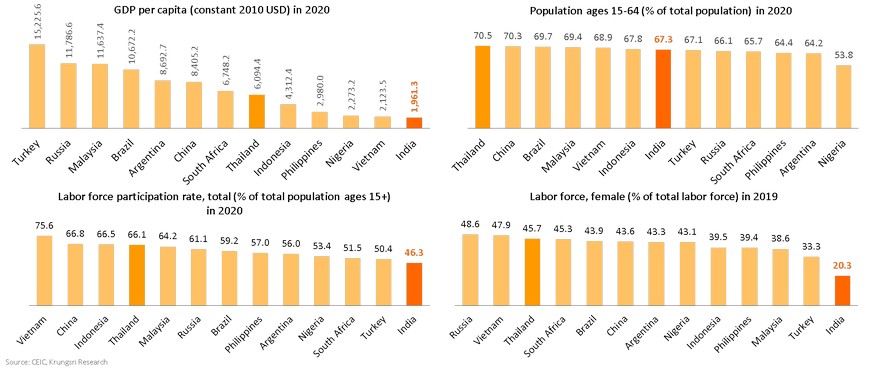

India has a dynamic and sizeable domestic market which largely remains untapped

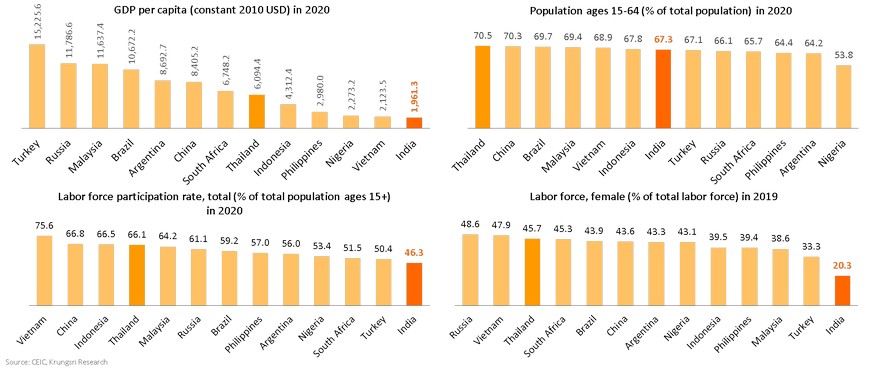

On the back of sustained and high growth periods, India’s GDP per capita (constant 2010) has increased to reach 1,961.3. Despite being the lowest among comparable global peers, the figure highlights a growing purchasing power of local consumers. In 2020, India has a labor force (population ages 15-64 years old) of 67.3% which is relatively high. However, the country’s labor force participation rate is surprisingly low, at about 46% in 2020. In addition, India has a low level of female labor force and there is only about 20.3% of the female total labor force in 2019. Looking ahead, with different initiatives and structural reforms including promoting employment in the formal sector, labor force participation rates could rise on the horizon.

Recent Economic Developments

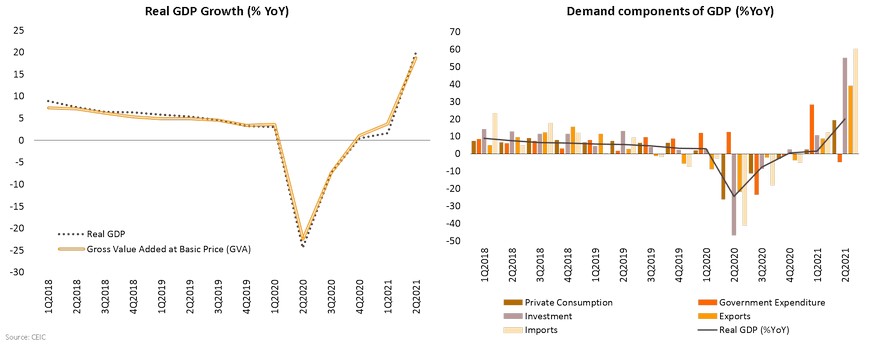

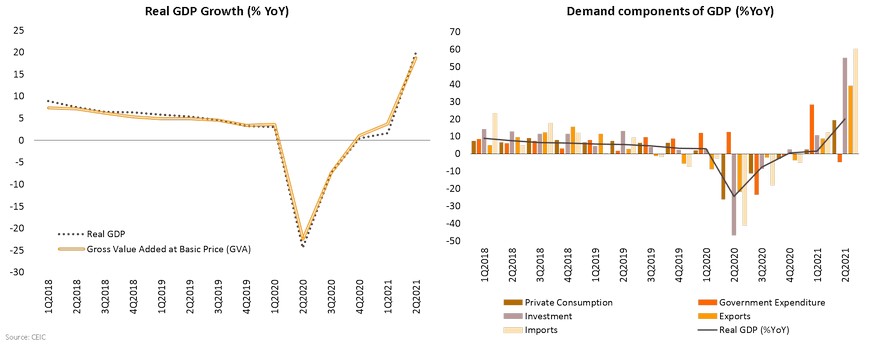

The economy hit hardest by the pandemic with the slump of -7.3% YoY in the FY2020/21 is on the recovery path

India’s real GDP increased by 20.1 % YoY in 2Q2021 on a calendar basis (corresponding to 1Q of the current fiscal year 2021/22 in the April-June quarter), expanding further from 1Q 2020 growth of 1.6% YoY. For the whole fiscal year FY2021, ending in March 2021, the economy registered a contraction of 7.3% YoY. Based on the latest figure, despite of a low base in 2020, the overall economic activity has gained momentum to exit the pandemic-induced crisis in the FY2021/22. According to the IMF, India’s real GDP is projected to grow by 9.5% in FY 2022 (starting in April 2021 and ending in March 2022) and 8.5% in FY 2023.

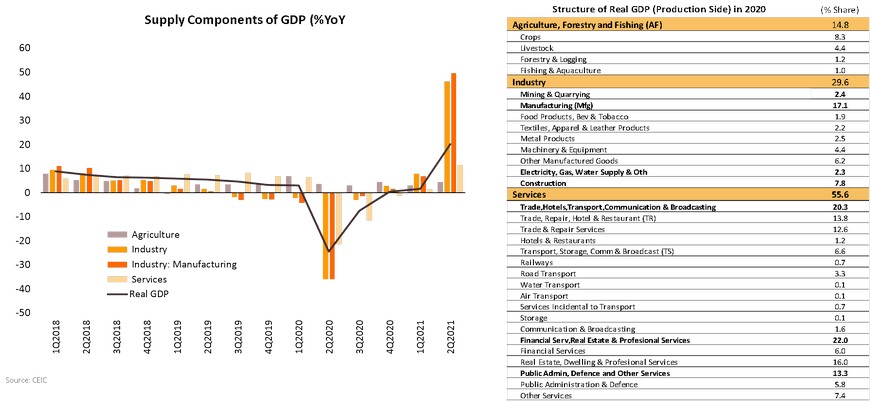

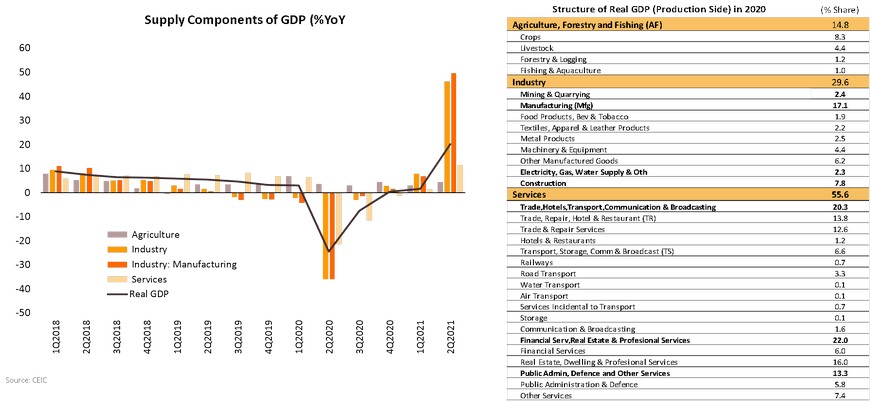

Due to the pandemic, all economic sectors have plunged into a negative growth territory, but recent figures released confirm the recovery

India’s economy on the supply side showed a sign of strong rebound following the deep decline in 2Q2020. However, due to some restrictions on mobility and containment measures, the pickup of activities in the services sector remain fragile. On the structure of the supply side of the economy, agriculture, industry and services account for 14.8%, 29.6%, and 55.6%, respectively, in 2020.

Economic activity in 2Q FY2021/22 confirms the recovery amid headwinds to growth, particularly the pandemic and its new variants

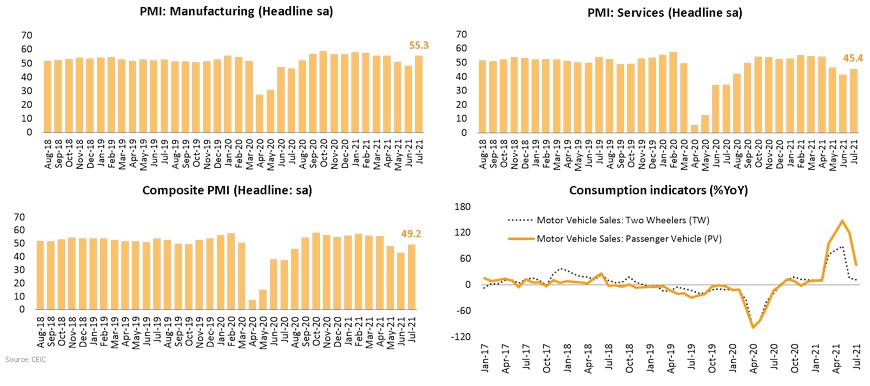

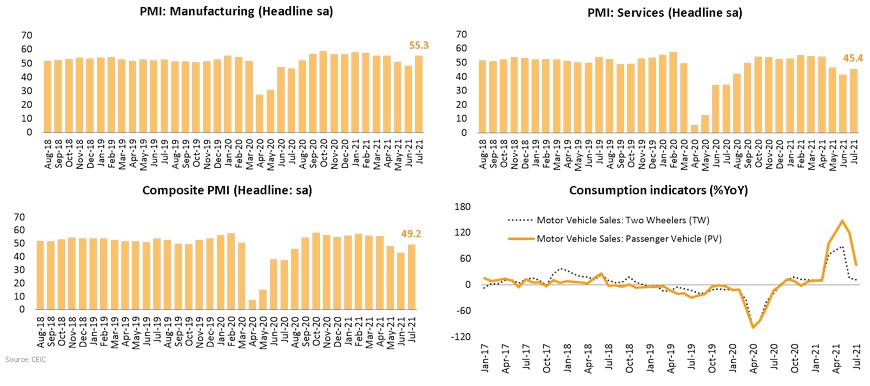

The latest PMI: manufacturing in July 2021 has surged to 55.3 above the level of 50 which indicates the expansion compared to previously month reflecting the rebound in the industrial sector. However, activity in the service sector remains weak reflected by the PMI: Services which has been blow the level of 50 in July at 45.4. Overall, the economic activity is gradually recovering. Household consumption which is the largest growth driver on the expenditure side has also showed signs of recovery.

High-frequency data confirms the normalization of India’s overall economic activity

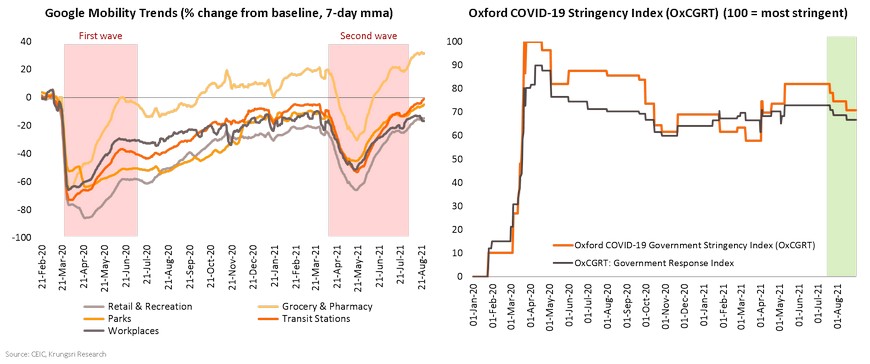

Due to a gradual relaxation of mobility restrictions and the recent re-opening of the economy following the second wave in late March-April 2021, economic activities in India are starting to normalize reflected by the latest Google Mobility Trends and the Oxford COVID-19 Government Stringency Index. Looking ahead, we expect the pace of economic recovery to gain further traction nurtured by a meaningful progress of vaccinations across the country, but risks remain against the backdrop of the spread of the delta variant.

Progress of vaccination rollout amid the emergence of new variants of the pandemic would be a key to nurture the sustainable economic recovery on the horizon

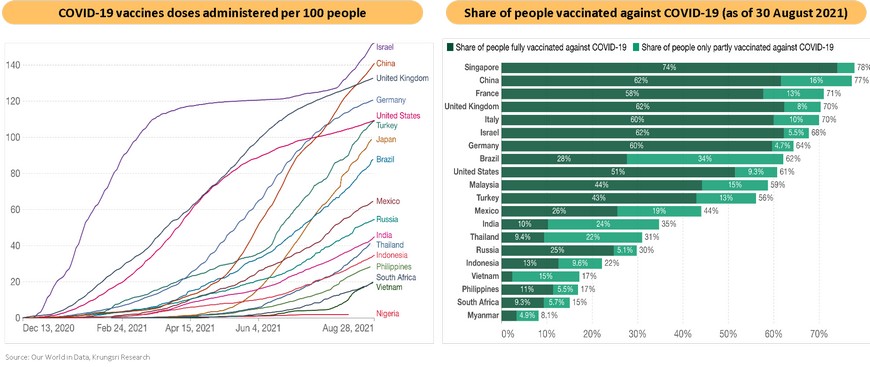

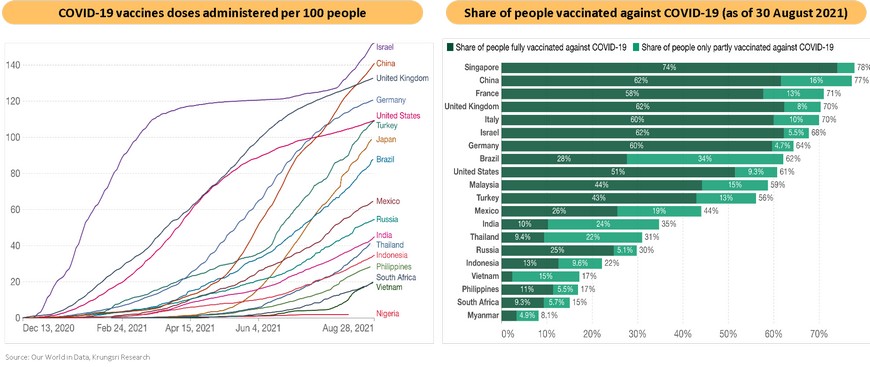

Vaccination progress in India have on on the rise and there is about 35% of the population partially vaccinated. But the population fully vaccinated remains relatively low, only 10% (as of August 2021). Looking ahead, with the current pace of vaccination rollout, the share of fully vaccinated population is likely to increase, and this would subsequently accelerate the rebound of domestic demand.

Fiscal deficits have been lingering worsened by the pandemic-induced recession on the back of twin deficits

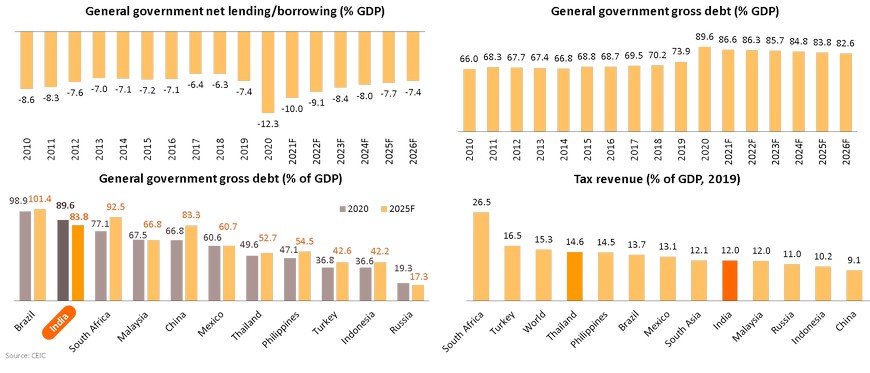

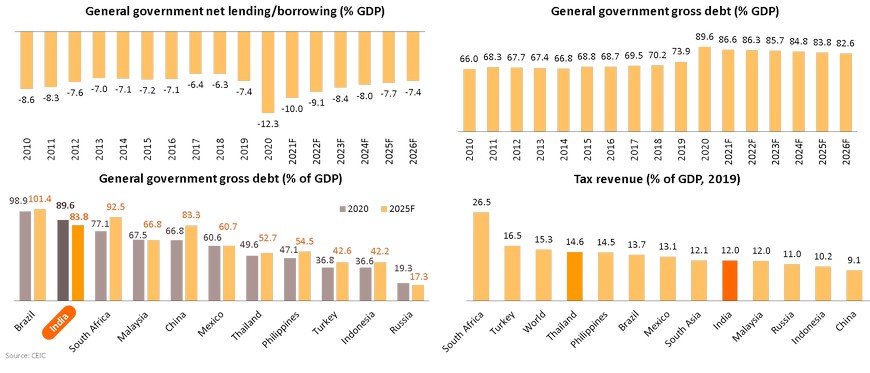

Based on the IMF data, the government run -12.3% of GDP of budget deficit in 2020, the most sizeable gap over the past decade. Against the backdrop of the pandemic-induced recession, the public debt (% GDP) reached almost 90% and India's public debt seems relatively large in comparison with other major emerging market peers. However, to contain any on concerns of fiscal sustainability, the Indian government has made efforts to adhere to fiscal discipline and its headline fiscal deficit objective as well as agree to pursue medium-term fiscal consolidation.

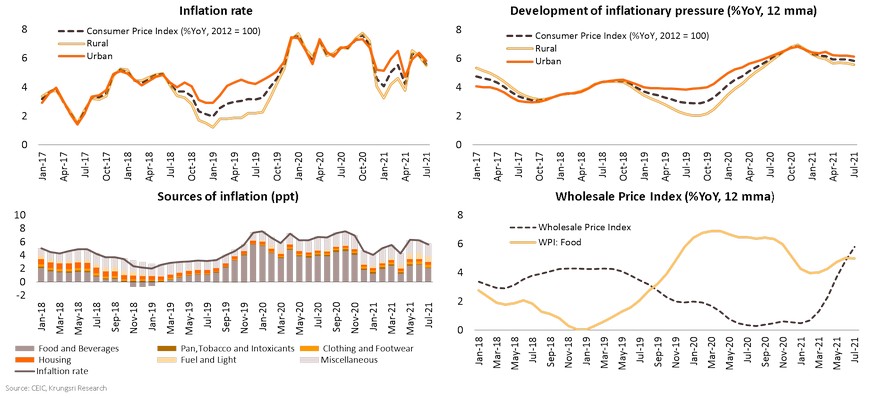

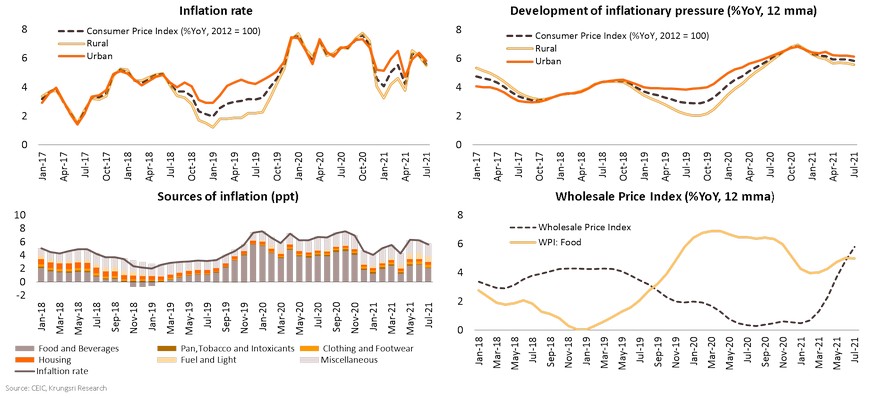

Surge in inflationary pressure driven largely by food prices appears to be contained

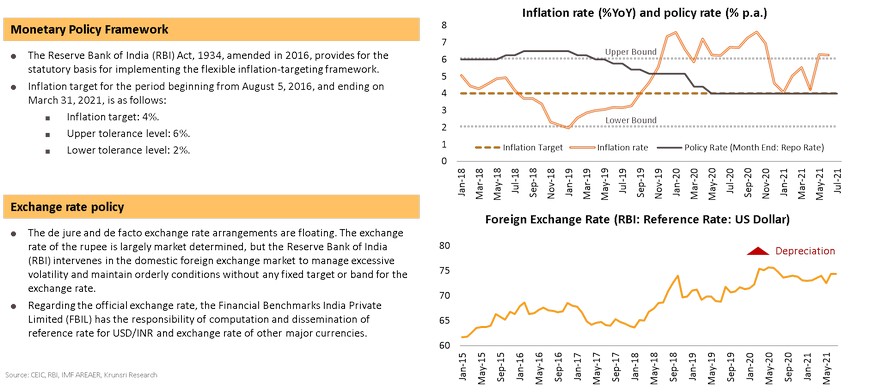

India’s recent inflationary pressure has been driven by food prices. The inflation rate has decelerated to 5.6% YoY in July 2021 from 6.3% YoY in June. Looking ahead, the inflationary pressure appears to abate and move toward the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) ’s target range of 4% +/-2%. However, upside risks remain given domestic demand is picking up.

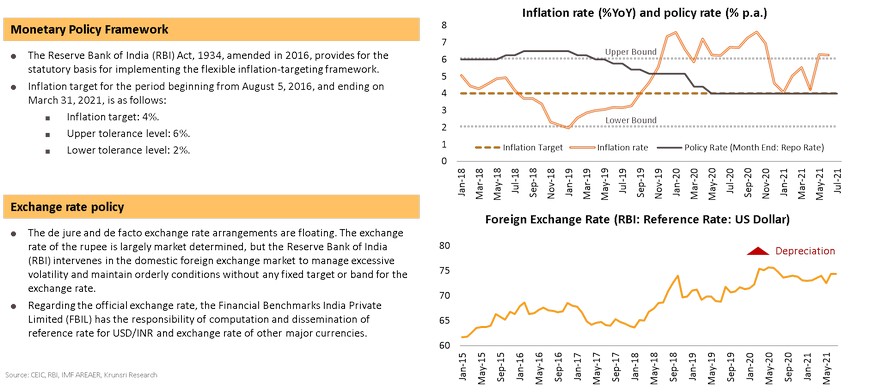

The flexible inflation targeting has served the country well in preserving price stability

India formally adopted flexible inflation targeting (FIT) in June 2016 to preserve price stability, defined in terms of a target CPI inflation, as the primary objective of monetary policy. The RBI, the central bank’, has adopted the 2%-6% target range over the medium term to guide its monetary policy conduct. While there are short-term fluctuations of inflation rate, the FIT has seemed to successfully help contain inflation expectations in India so far.

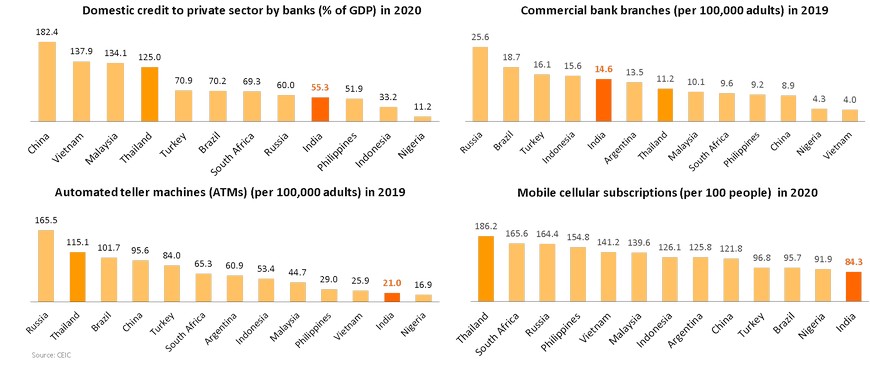

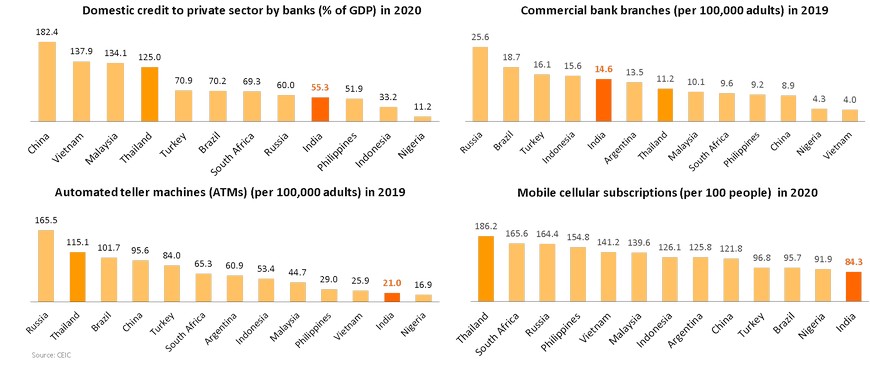

The financial sector can be developed further to achieve better inclusion and access to financial services

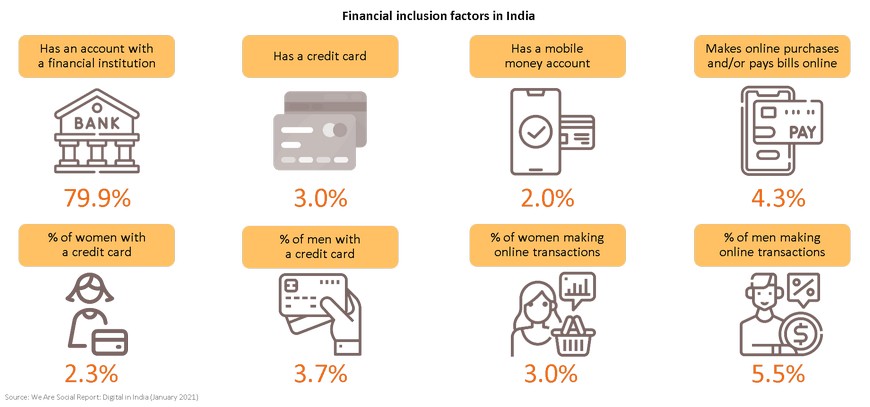

The banking sector in India appears to have less dominant role in supporting the economy compared to that of global peers with the ratio of domestic credit of 55.3% of GDP, compared to 182.4%, and 137.9% of China and Vietnam, respectively. In addition, the issues of financial inclusion – particularly access – have sizeable room for developments through mobile-led modes and digital financing given a relatively high mobile subscriptions.

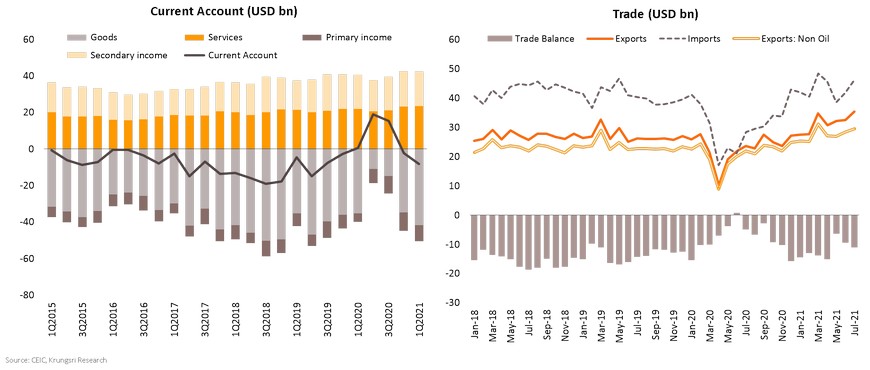

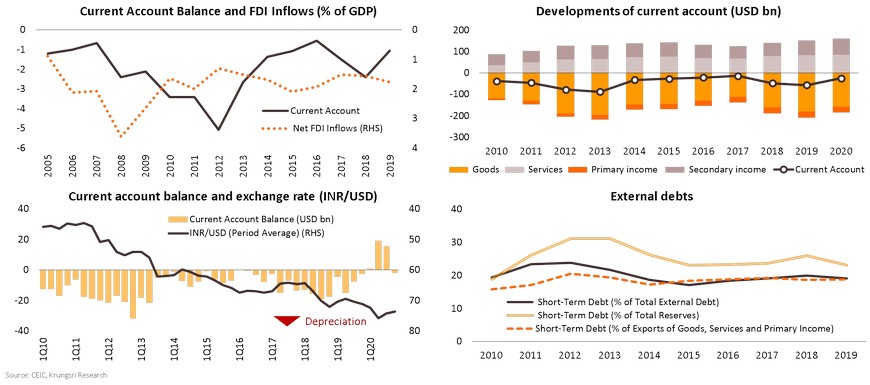

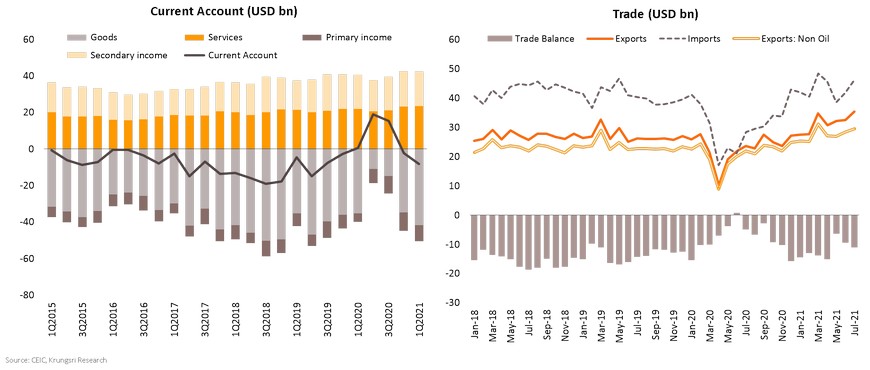

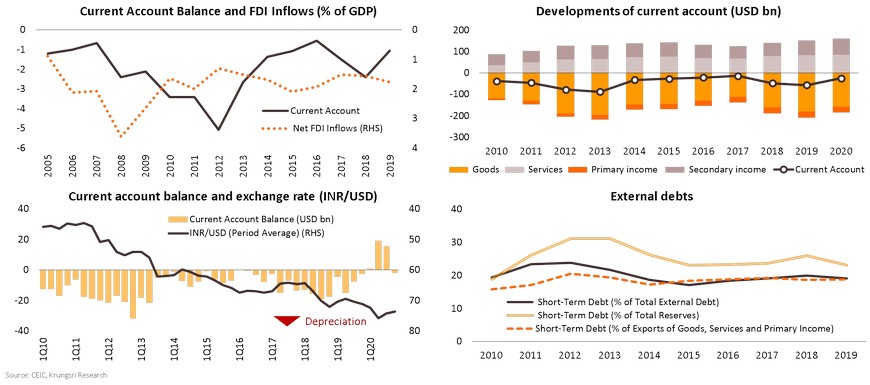

Persistent deficits of trade in goods have primarily led to prolonged current account deficits

India have suffered from prolonged current account deficits (CAD) against the backdrop of persistent government budget deficits leading to chronic twin deficits. Occasionally, these have fueled external instability and put downward pressure on the exchange rate. However, the overall external stability remains sound due to sufficient foreign reserves and low external debts.

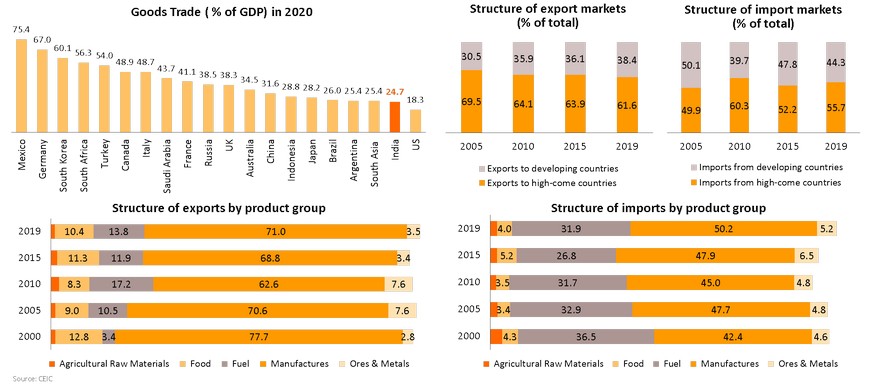

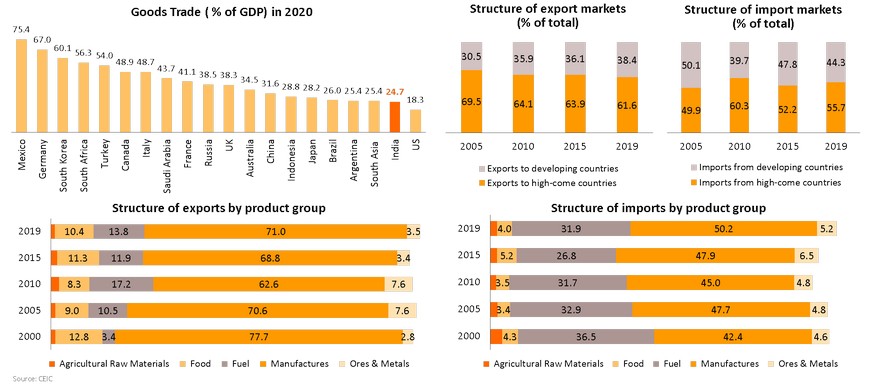

A degree of trade openness may reflect structural bottlenecks and impede Indian businesses to be integrated into global and regional supply chains

India has a relatively low degree of trade openness in relative to that of peers, with the ratio of about 25% in 2020. This may limit opportunities of India to reap the benefits of international trade.

The overall external stability remains fundamentally sound amid lingering current account deficits

Despite persistent current account deficits (CAD), the external sector stability remains relatively sound due to adequate levels of international reserves and low external debts. In addition, FDI inflows have played significant roles in supporting India’s external sector stability by sufficiently financing the prolonged CAD.

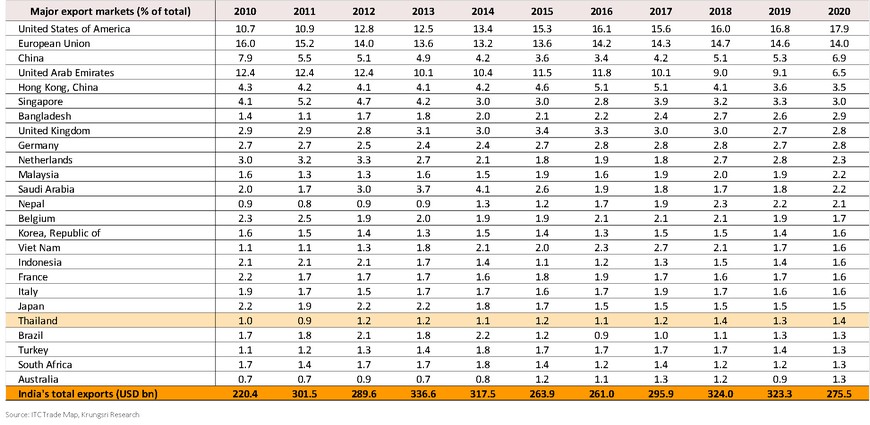

The US and the EU are the two largest export markets for India

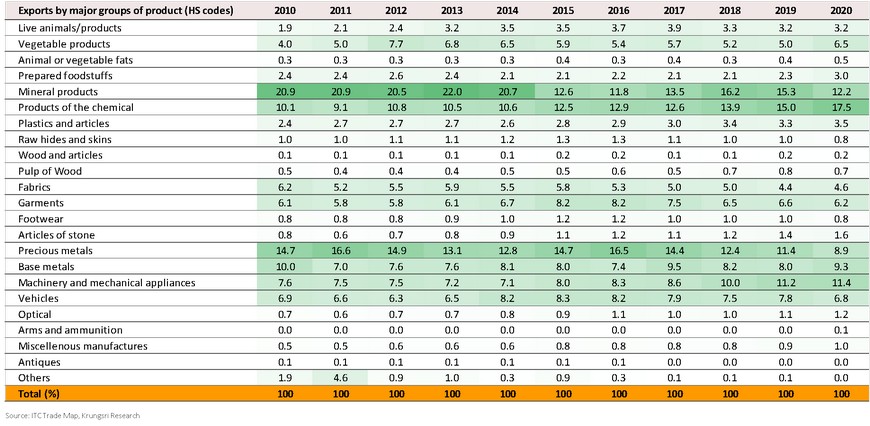

Chemical and mineral products dominate India’s exports

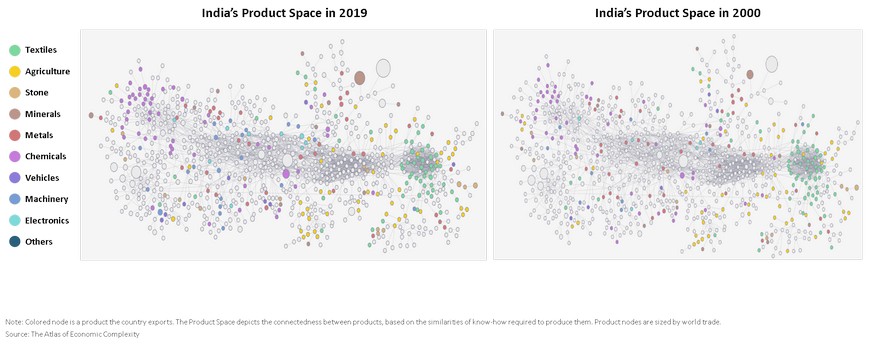

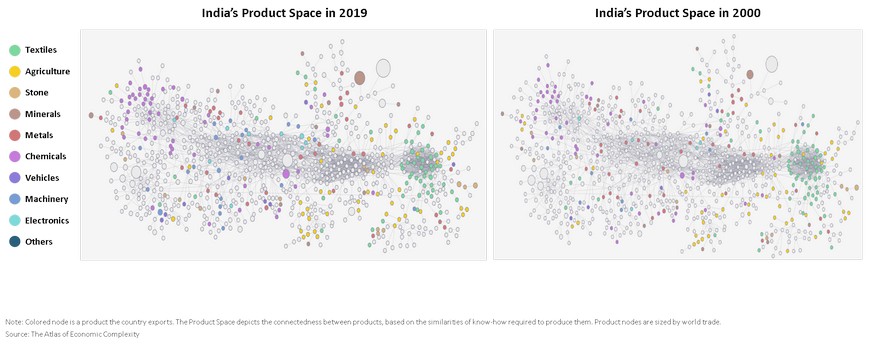

The export structure has not been changed significantly over the past two decades

Since its economic reforms in the 1990s, India has not been successful in developing its manufacturing sector reflected by the manufacturing’s share stagnated at around14-16% of GDP since the 1970s. In addition, this could be reflected a visualization called product space depicting the connectedness between products, based on the similarities of know- how required to produce them. India exports at the core of the product space have been concentrated on chemicals and textiles. This structure have not been changed significantly in 2019 compared to that in 2000. However, reforms including the Make in India Policy could help boost the development of the manufacturing sector in the country.

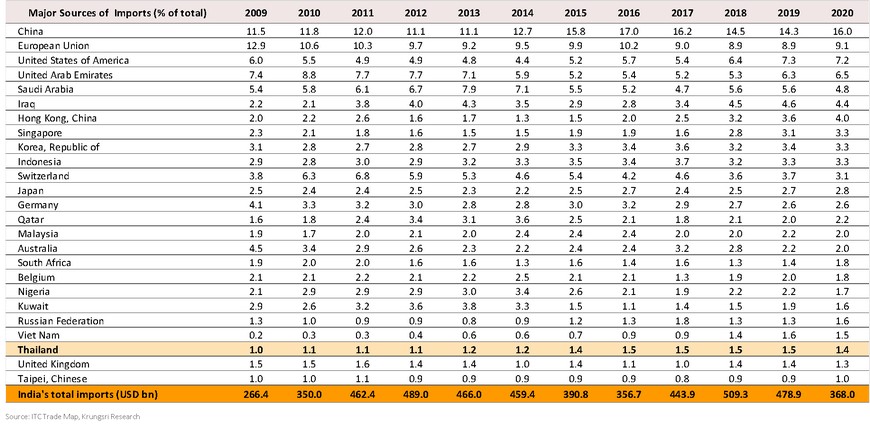

China is the single largest source of India's imports

India’s import structure by major product group reflects its export structure

Medium-term prospects

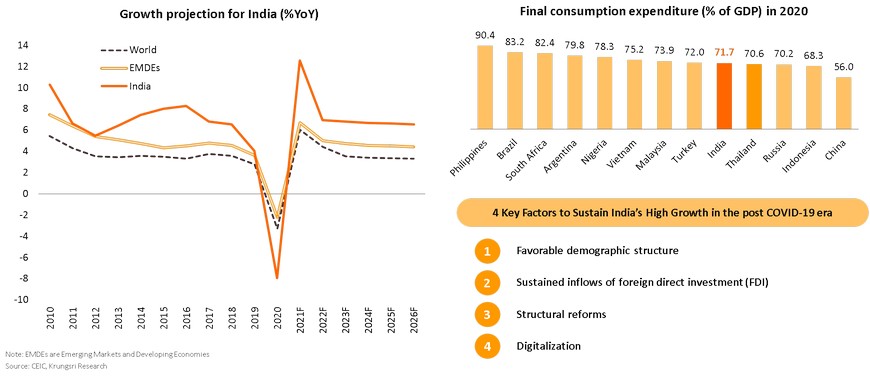

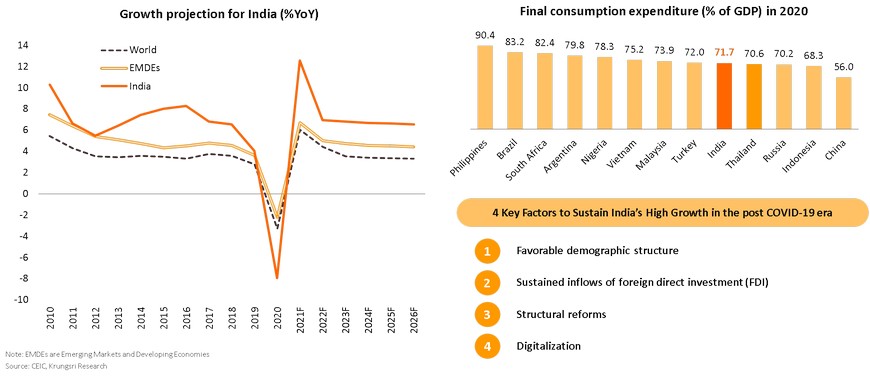

Long-term growth prospects for India remain favorable due to India’s fundamental factors

Despite economic scars caused by the pandemic, the outlook for India’s long-term growth remains favorable and the economy could expand by 5.0 – 6.0% p.a. which is slightly below the growth trajectory in the last decade (2010-19) of about 7.0 – 7.5 % p.a. India’s longer-term path will be boosted by its favorable demographic structure, foreign direct investment (FDI), structural reforms, and digitalization and modernization of the economy .

Demographic advantage has put India in a competitive position to drive its manufacturing sector and its digital economy

India is projected to add more than 100 million population to its workforce by 2030. While it could be challenging for the authorities to generate large job opportunities, India has opportunities to reap a demographic dividend. But low labor force participation rates and poor access to education could impede the contribution of labor supply to growth. On the other hand, while the economy is heading back to its high potential path, it is expected that the number of households with an income greater than USD30,000 is likely to more than double over the next decade.

1. Favorable demographic structure

Sizeable middle-class consumers continue to expand driven by sustained high growth

While decreasing, the share of agricultural employment has been large accounting for 42.6% in 2019 compared to about 60% in 2000. This would release workforce to more productive sectors including manufacturing and higher value-added services. By 2030, the structure of population will be favorable with sizeable young and wealthier workforce as about two-thirds of population is below 35 years with the average age of 25 years old. The middle class is on course to expand on the back of high growth.

2. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

FDI is concentrated on the ICT and financial and insurance sectors with the US and the UK as the largest investors

Structural reforms and initiatives implemented under the current administration of PM Modi have induced sizeable inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) to India. As of 2019, the secondary and the tertiary sectors are the largest beneficiaries of FDI with the share of 53.1% and 46.4%, respectively.

2. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

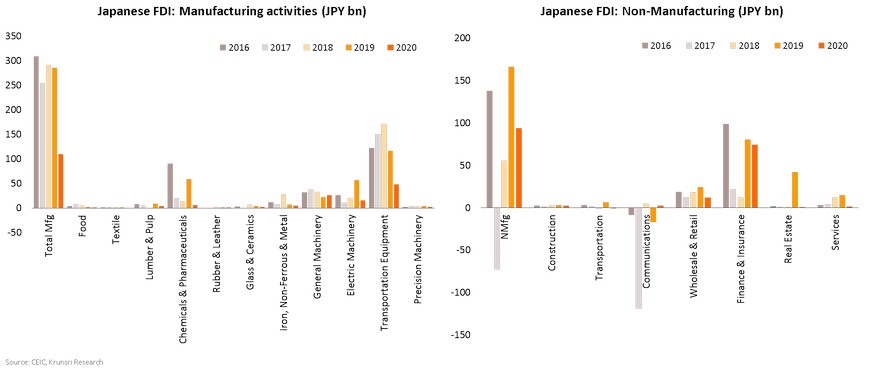

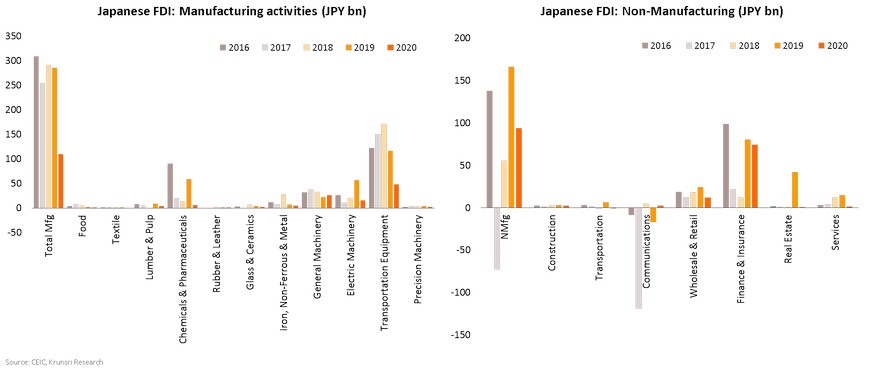

Japanese Direct Investment has been concentrated on the transportation equipment on the manufacturing, and on financial and insurance sector on the non-manufacturing

Currently, Japan is the 5th largest investor in the India with cumulative FDI inflows of USD35.4bn over the past two decades accounting for about contributing 6.7% to India's total FDI outstanding in 2020. Since the launch of the Make in India Initiative, Japanese direct investment to the country has continued to rise both in the manufacturing – particularly the transportation equipment- and non-manufacturing – especially finance and insurance- activity.

2. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

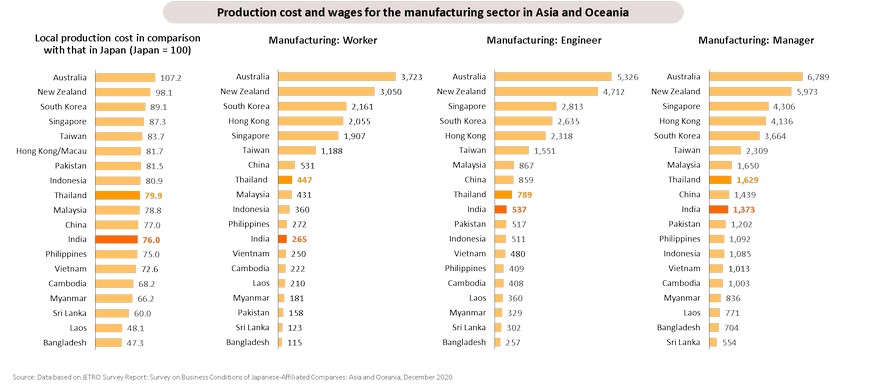

Costs of production is relatively low and provides India competitive advantage as an investment destination labor-intensive manufacturing sector

2. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

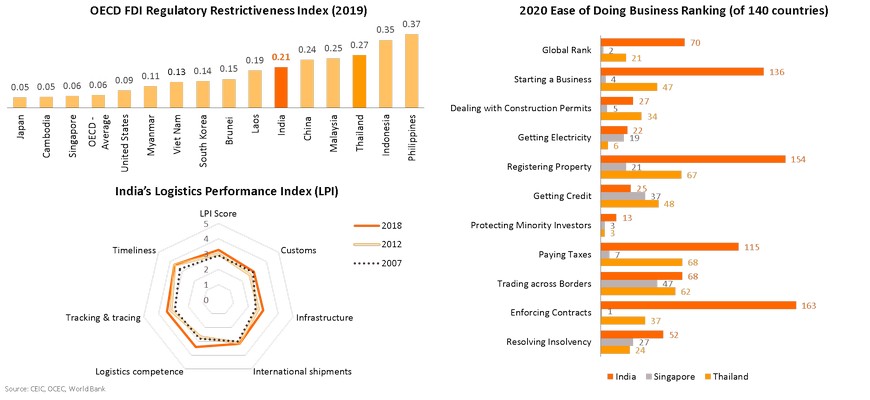

Business environment is relatively conducive as regulatory restrictiveness has been lowered as a result of ongoing structural reforms

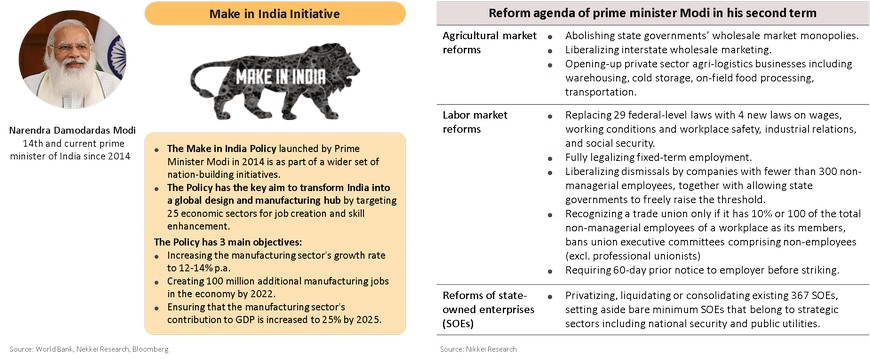

3. Structural reforms

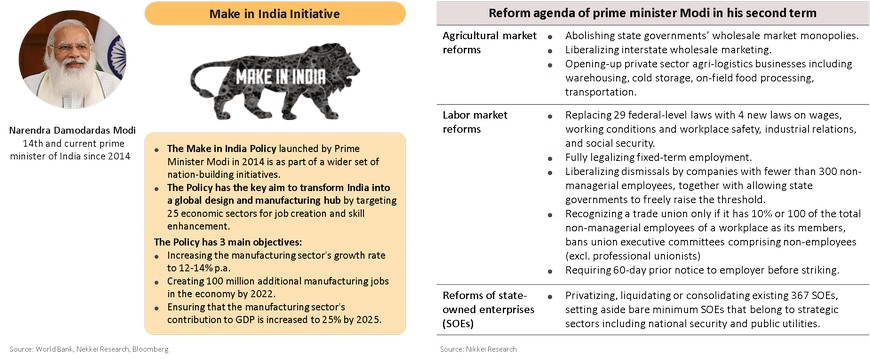

Reforms initiated under PM Modi could unlock India’s structural bottlenecks and realize its full growth potentials

Since taking office in 2014, the Modi government has introducing and prosecuting an ambitious economic reform agenda aiming at bringing more local businesses into the formal economy, divesting the government's stake in public sector companies, increasing Goods & Services Tax (GST) compliance, and stabilizing the financial sector. In this second term following the landslide victory in the recent general election in 2019, the government has introduced additional reforms including liberalizing domestic agricultural markets and easing labor regulations, as well as reforms to education policy. These measures could significantly unlock structural bottlenecks and boost India’s potential growth.

4. Digital economy

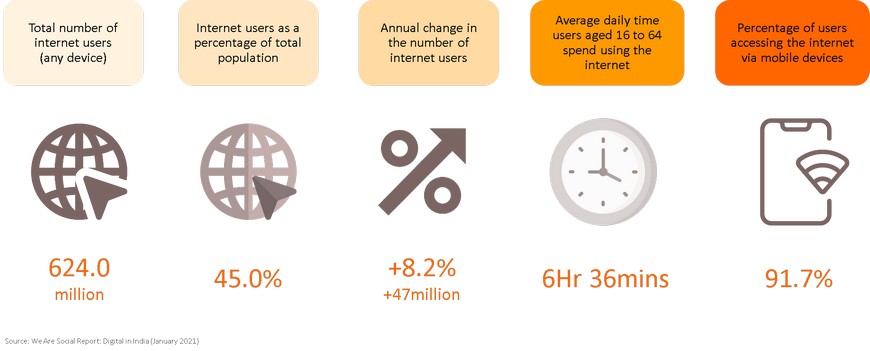

Digitization could provide a significant boost to India’s economic growth on the horizon

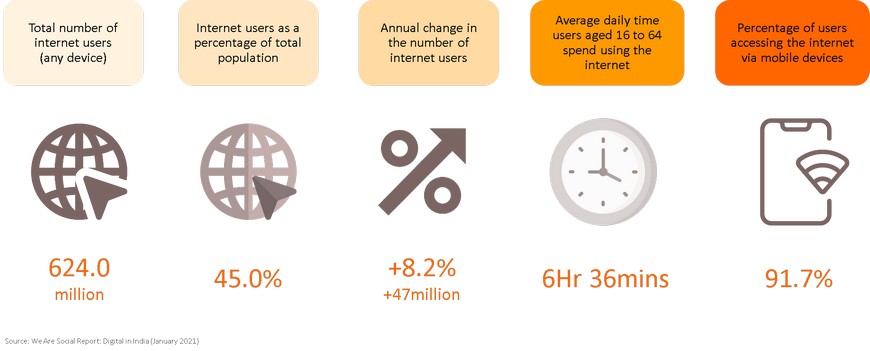

India’s digital market potentials have been driven by the considerable number of internet users of 624 million in 2021. As a result, India is among one of the largest and fastest-growing markets for digital consumers second only to China. In addition, the government under PM Modi launched the Digital India Initiative in 2015 to promote e-services provided by the public sector as well as to improve digital infrastructure including internet connectivity and digital literacy to drive the digital adoption. Undoubtedly, digitalization has huge potentials to drive India’s long-term growth.

4. Digital economy

Digital technology is expected to play significant roles in delivering better financial services and promoting financial inclusion in India